Paving the Way for PNC Park

November 28, 2023

This article was originally published in the May/June 2001 issue of DEMOLITION magazine, back when the National Demolition Association (NDA) was the National Association of Demolition Contractors (NADC).

Pittsburgh’s Three Rivers Stadium, located where the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers join to form the Ohio, was one of the last remaining “all-purpose” stadia, designed for every possible use from pro football to rock concerts. Similar to Cinergy Field, formerly Riverfront, in Cincinnati and Veteran’s Stadium in Philadelphia, Three Rivers had outlived its usefulness and the taste of its fans. As part of Pittsburgh’s Renaissance, the Steelers and Pirates opted to build individual stadia with grass fields and more user-friendly facilities.

Built in the 1970s, Three Rivers hosted the likes of Terry Bradshaw and Rocky Bleier. It was the site of Franco Harris’ famous “immaculate reception” in 1972 and the Steel Curtain defense. Mean Joe Greene and Jack Lambert prowled its gridiron as Art Rooney’s Steelers marched to an unprecedented four Super Bowl titles. In those days, as now, everyone in western Pennsylvania donned black and gold on Sunday morning. Priests would treble their Saturday masses in the fall so no one missed any of the excitement on Sunday. During the 1970s, the Steelers won 45 games at Three Rivers, losing only six.

When the Pirates played at Three Rivers, they won two World Series in the 1970s with the help of fist round Hall of Famer Willie Stargell and their theme song, “We Are Family.” Pittsburgh began to call itself “The City of Champions.”

But times were changing in the Steel City. The mills that ran along both sides of the three rivers were closing. Dirty, sulfur-laden coal was being replaced with natural gas to fuel steel furnaces. The greener pastures of the Deep South or overseas production beckoned the old Rust Belt steel companies. Between 1978 and 1985, Pittsburgh lost over 150,000 manufacturing jobs. The city itself is down to about 325,000 residents, less than half of its 1950 population.

In 1994, newly inaugurated Pittsburgh Mayor Tom Murphy was looking at a city in a downward spiral. With each mill closing, the city lost more ground in its efforts to attract or retain employers. Next came the news that the Pirates were for sale. To lose the venerable old Buc-Os to one of the Sun Belt cities of the New South or growing Southwest would have meant the end of Pittsburgh’s long tradition of professional sports.

New Pirates owner, 32-year-old Kevin McClachy, scion of a Sacramento newspaper family, made it clear that the Pirates were going to need a new stadium if he was going to keep them in Pittsburgh.

New Pirates owner, 32-year-old Kevin McClachy, scion of a Sacramento newspaper family, made it clear that the Pirates were going to need a new stadium if he was going to keep them in Pittsburgh.

McClachy made it clear from the start that the graceless, cold and cavernous Three Rivers was not a place for his baseball team. He characterized it like “sitting in a giant gray ashtray.”

With the advent of Camden Yards in Baltimore, the era of new, fan-friendly baseball parks with intimate sightlines and edible food gave Pittsburgh a glimpse of what was possible.

Now all that was left to do was convince Art Rooney that Three Rivers’ time was over and begin to raise the money necessary to build two new parks.

Three Rivers had been good to the Steelers. School children still visited it and field trips, and Rooney though it might be possible to rehabilitate the venerable old park for a football-only use. Just about the time estimates were being developed to perform this re-hab, Art Rooney realized that every other team in the Steelers’ division was building a new stadium, each guaranteeing new revenue streams. No stranger to the money wars of the NFL, Rooney ordered plans for a new state-of-the-art football-only park for his beloved Steelers.

Next, the money. An 11-county referendum was placed on the ballot in western Pennsylvania only to fail miserably as voters questioned the need to support the “rich owners” in their quest for more money.

Mayor Murphy joined with the business community of Pittsburgh to convince the Pennsylvania Legislature that Pittsburgh needed to maintain two professional sports teams to keep the western half of the state strong and growing. The Legislature in Harrisburg came through and authorized enough money for Pittsburgh to begin the building of two new parks. Now it was up to the mayor and the news sports teams to convince the people that had just voted not to approve the new parks that the future of their region depended upon these projects.

The “Deconsecration” of Three Rivers Stadium began on December 17, 2000, when NADC member Bianchi-Trison Corp. of Syracuse, New York, signed the contract for the demolition of the stadium. Soon the AstroTurf playing surface that once held the likes of Frenchy Fuqua and Franco Harris was torn up for use in city parks and Little League fields.

On January 15, 2001, after the city and teams had conducted an auction of Three Rivers memorabilia, Bianchi-Trison began working with fellow NADC members Project Development Group Inc. of Monroeville, Pennsylvania, who performed the complete removal of all above-ground hazardous waste and the asbestos abatement, which included the entire roof, and Controlled Demolition Inc. (CDI) of Phoenix, Maryland, who was going to perform the implosion.

David Bianchi of Bianchi-Trison mobilized his crew to prepare the site for the implosion. Working under a contract with a $15,000-per-day liquidated damages clause and the Steelers new football stadium located only 80 feet away, he brought some 210 workers to the site.

Working 24 hours a day, CDI’s crew drilled 2,500 holes in the concrete columns of the stadium’s five concrete levels for the 4,800 pounds of explosives CDI used to bring the structure down. Each of the columns were wrapped with chain-link fence and geotextiles fabric to prevent flying debris.

Bianchi-Trison has had considerable experience working with implosion projects, performing work on public housing units throughout the Northeast, so they knew just what to expect at Three Rivers.

Bianchi-Trison wired cable around the access ramps to the stadium so that they would be pulled inward during the implosion.

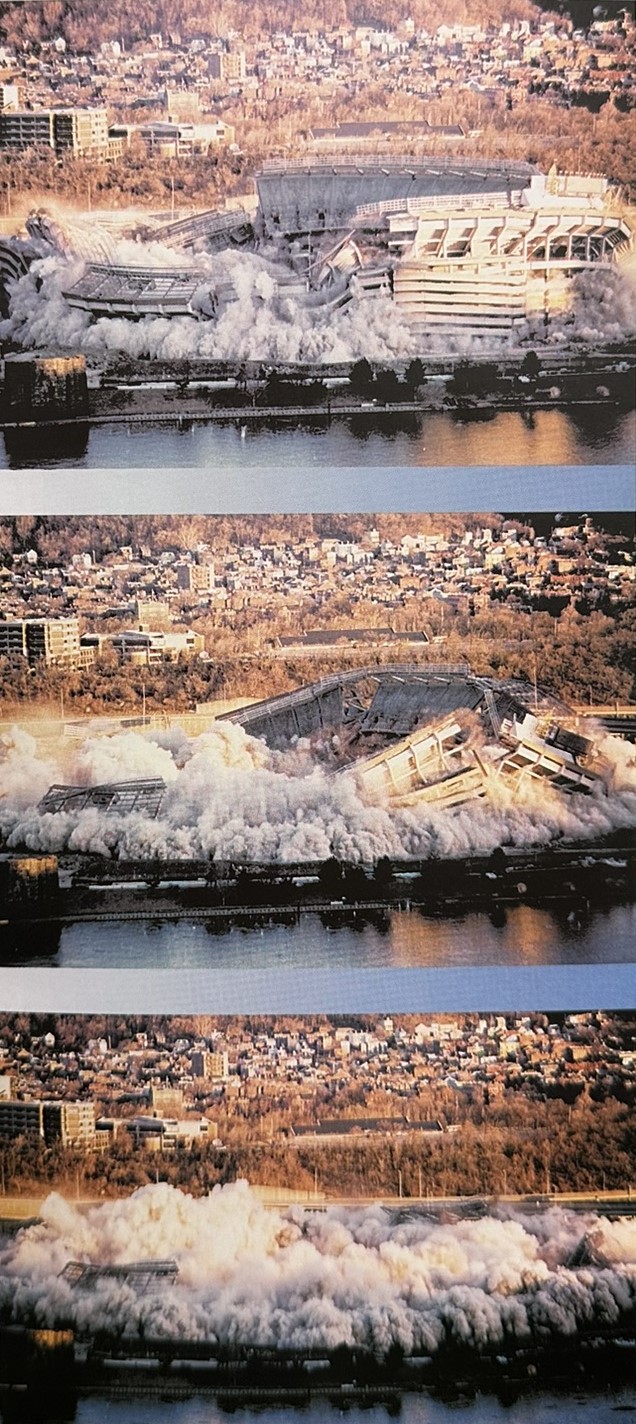

Fighting a 33 calendar day schedule, CDI brought the massive 30-year-old monster to its knees at 8 a.m. on Sunday, February 11, 2001. A crowd of over 25,000 watched from both sides of the river as Three Rivers fell inward onto its old playing surface.

Now Bianchi-Trison faced its biggest challenge: how to move almost 200,000 cubic yards of debris and finish all necessary site work by April 27, 2001.

Mobilizing a fleet of excavators including a Komatsu PC 1000 outfitted with a 7.5-cubic-yard bucket; two Komatsu PC-750s equipped with grapples and universal pulverizers; five PC400s; three PC300s assigned for general cleanup; four CAT 235 loaders; two CAT 46s; and a CAT 330, Bianchi began to get a handle on the tangled debris pile facing it.

Using these 16 pieces of high-tech equipment, Bianchi-Trison processed an estimated 6,000 tons of structural steel, 4,000 tons of rebar and close to 180,000 tons of concrete. An additional 60,000 cubic yards of waste material was processed on-site for use as refill.

Bianchi-Trison completed all this work in a record-breaking 25 days with an average of 300 loads per day of concrete and 50 loads of steel moved off-site. By completing the project in record time, Bianchi received a hefty $100,000 bonus for making the deadline.

David Bianchi wanted to extend a special thanks to Don Schulick, project superintendent, and Team Bianchi that went the extra mile on this project. He also wishes to thank the Loizeaux family and everyone from CDI; the people of PDG from Monroeville; Locals 66 and 373; AMEC; and the Sports and Exhibition Authority of Pittsburgh for making this project a success.

Team Bianchi can proudly say that it played the final game at Pittsburgh’s Three Rivers Stadium.