Leveling the Palisades

May 24, 2022

This article was originally published in the June 1995 issue of DEMOLITION magazine, then called Demolition Age.

The market for the association’s implosion contractors seem to grow and grow. If you look at some recent back issues of Demolition Age, you’ll find stories on the Christopher Columbus Housing Project in Newark, the old Sears Distribution Center in Philadelphia and the Cuneo Press Buildings in Chicago. Future stories will tell the tale of implosion at the Raymond Rosen Housing Project in Philadelphia and the Met Center in Bloomington, Minnesota.

More and more municipalities are accepting implosions as a safe and effective way of bringing down large structures. Because of the often dramatic nature of implosions, they have become the demolition method of choice for some clients. Certainly in Chicago, which had never permitted the use of explosives in demolition, the implosions of the Cuneo Buildings were orchestrated by Mayor Daley himself to publicize his administration’s plans to remove distressed properties from the city’s tax rolls.

Likewise, the implosions in Newark, Philadelphia, East St. Louis and other cities with large high-rise public housing blocs are part of the Department of Housing & Urban Development’s efforts to tell the country that they have abandoned the use of high rises in public housing. HUD is interested in sending this message in the most dramatic way possible.

In many cases, however, implosion is chosen because it is perceived as the quickest way to bring a structure down. A number of cities that have had prior experience with implosions often prefer it as opposed to conventional demolition, which obviously takes longer. Vancouver is one of these.

Geopolitics plays a significant role in the rapid expansion of the “Jewel of the Canadian West.” In 1997, the People’s Republic of China will take possession of the former Crown Colony of Hong Kong after a 99-year lease maintained by Great Britain, granted after the Second Opium War of 1897, lapses. Many wealthy residents of Hong Kong, reluctant to take a chance on the whims of the Communist leaders in Beijing, have opted to emigrate. Vancouver has become a welcome haven for many.

This influx of new, well-to-do emigres has driven the demand for housing in Vancouver through the roof. Which brings us to the Pacific Palisades apartment complex.

Located on Vancouver’s fashionable West End, this 23-story apartment complex was less than 25 years old and still looks as modern as the rest of Vancouver’s skyline. However, Malaysian developer Robert Kuok knew a good location when he saw one. He began planning for two residential towers, one 26 and the other 34 stories tall, both condominiums.

Insisting on a very tight schedule, Kuok let a contract to NDA member Pacific Blasting of Vancouver to bring down the 23 story apartment complex and a neighboring five-story hotel.

Following a strip-out and auction of all furniture by the owner, Pacific moved in to prepare the building for implosion.

First, their salvage crew moved through the structure, removing all sinks, kitchen cabinetry and the like, for resale. Next, in order to comply with British Columbia’s strict rules concerning the disposal of drywall, Pacific removed all the plasterboard in the building and lowered it through the building’s elevator shaft.

Current B.C. Ministry of the Environment regulations require the recycling of all building components, where practical, and prohibit the disposal of drywall unless the disposal facility maintains 100% leachate collection and control, rare in western Canada. The Ministry believes that, as all ground water eventually flows to the sea in B.C. and drywall has a nasty habit of leaching into the groundwater of disposal sites, every effort should be made to recycle the material. Drywall recycling in B.C., however, is not cheap. Local recyclers want between $70 and $100 a ton to take the material.

The law being the law, Pacific began the removal of all plasterboard in the complex. They decided at the same time that, as they wanted to recycled the concrete and wood fraction of the structure, they would remove all the interior partitions in the building before the implosion. This would make the re-use of the concrete and wood just that much easier.

Once the strip-out was completed, the only thing left to remove were the windows. As Jim Redyke of NDA member Dykon Inc. of Tulsa, Oklahoma, Pacific’s implosion subcontractor, began to prepare the Palisades, demolition crews completed the removal of all windows in the complex.

In order to protect the swimming pool area of a neighboring hotel from the debris of the implosion, Pacific built a huge “blast wall” some 35 feet high and 90 feet long. Made from rented railroad ties, the wall involved the use of 16” I-beams driven 2 or 3 feet into the ground and the sliding of 12” thick railroad ties in between the angles of the beam. Pacific used double ties for the first 20 feet and single ties up to the 35 foot level. This massive protection screen guarded the pool area of the nearby hotel and protected the facility’s generator room, steam room, and other mechanical spaces.

After Pacific drilled innumerable holes in the Palisades concrete and slab structure, Dykon’s team placed approximately 175 pounds of explosives throughout the complex. Most were places on the fifth floor and in the building’s basement, where it was strongest.

On the morning of Sunday, Nov. 13, crowds began to assemble. Nearby hotels were booked solid with people interested in a close-up view of the implosion. Sixteen-year-old Tanya Davis, recovering from cancer treatment, was on the wish list of Vancouver’s Children’s Wish Foundation and was chosen to push the button that would charge Dykon’s detonator. Dr. Don Johnson, who had paid $9,000 at a local charity auction for the privilege, was set to push the actual charger.

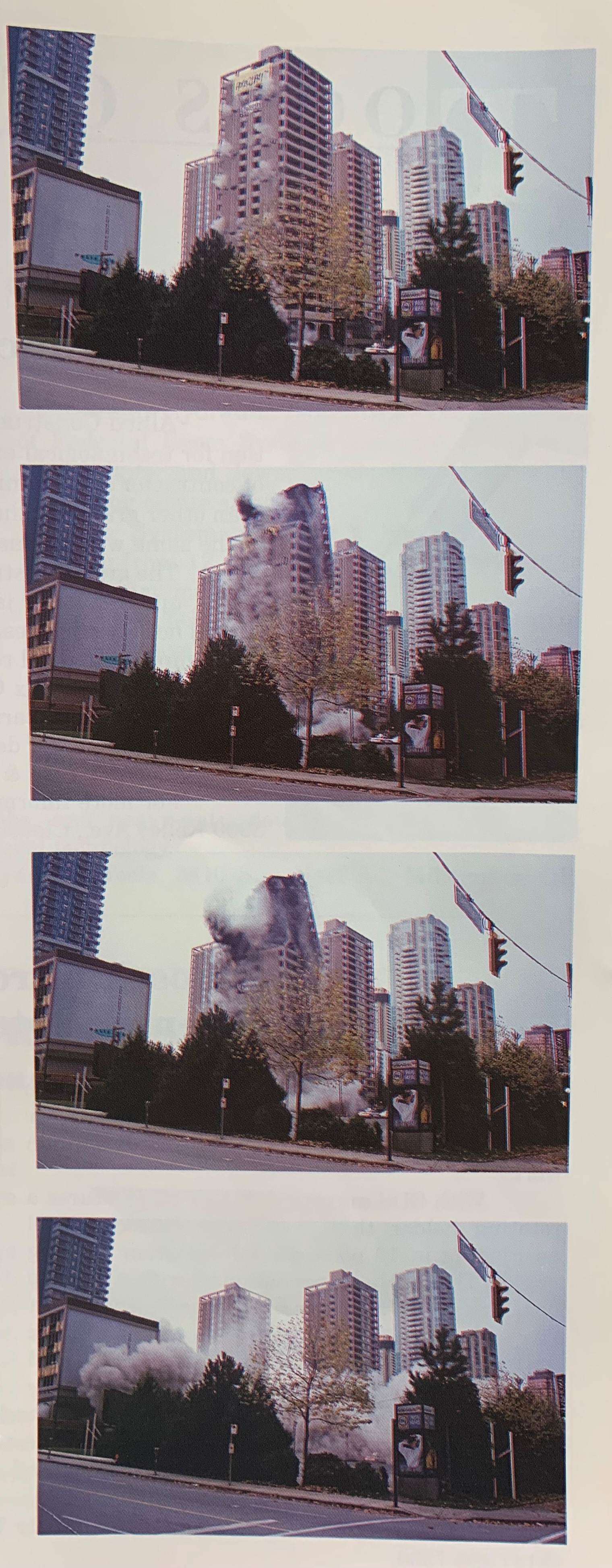

At exactly 8:30 a.m., Dr. Johnson pushed Dykon’s amber button down, and the Palisades settled into history. “The top of the structure nodded over, hesitated, then dove into the rising skirt of dust and debris that billowed up toward it.” At least that is how the Vancouver Sun eloquently described it.

The implosion produced a beautiful debris pile centered on the building’s footprint. People from Pacific Blasting were surprised at the state of the concrete from the building. It appears almost ready to be graded for reuse. Bringing in a LaBounty UP-90 on a John Deere 992, Pacific prepared the concrete fraction for reuse at a fill site established between two piers by the Port of Vancouver, less than 15 minutes from the job site.

Pacific had less than seven weeks to complete the preparation, implosion and site clearance. They also had to bring down the neighboring five-story hotel on-site, using conventional means, in that same time frame.

The cooperation from the city of Vancouver and the surrounding properties was outstanding. Local municipal officials, who had previous implosion experience and had developed procedures concerning street closing, police and fire department coordination, deposits for permits and the like, proved to be of great assistance to Pacific’s efforts. The nearby Blue Horizon Hotel booked rooms for the implosion and proved an excellent corporate citizen, helping Pacific in every way possible to pull off this difficult shot.

Jim Redyke of Dkyon has long experience imploding structures in B.C. and was a familiar and trusted face to local officials. He had done the Georgia Medical and Dental Building in downtown Vancouver some four years ago, and his success on that project held him in good stead for the Pacific Palisades job.

This complex implosion in a busy downtown area of a major city proved so successful because of the consistent cooperation between all the players involved and the professionalism of the firms doing the job. By now, implosions are standard operating procedures in B.C.