The Saga of Dayton Tire & Rubber

January 28, 2025

This article originally appeared in the July 1992 issue of DEMOLITION magazine.

In a classic economic treatise entitled “The Stages of Political Development,” political theorist A.F.K. Organski talks about the eras of economic growth that a nation state goes through as it develops. Organski theorizes that in a four-step process, an advanced economic state will arrive at what he calls a post-industrial era. This stage will be characterized by high technology, rapid communication and extended leisure time. It will also be a time of shrinking industrial production, the transfer of heavy industry to cheaper labor markets and a largely service economy. Organski predicts that the government will need to invent work for over 60% of its population in order to guarantee person fulfillment.

Whether you view the prospects of this “post-industrial” society with glee or dread, the United States is probably entering this era now.

While our national productivity has never been higher and the technological challenges of the 21st century are great, it is true that the service sector of the American economy is its fastest growing segment, and many of the high polluting, heavy industrial facilities have been moved offshore to countries with cheaper labor markets and less stringent environmental regulations.

The gradual dawning of this new era presents considerable challenges to the government agencies and the demolition industry that must deal with this epochal change in the structure of our economy.

This is the story of one small part of this change. Dayton, Ohio, is a medium-size city located on the banks of the Greater Miami River in southwestern Ohio, about an hour from Cincinnati. It is a pleasant place to live, with a university, nearby Wright Patterson Air Force Base and a corporate headquarters of NCR. It had, in the past, a thriving industrial base.

As the fortunes of industry changes and the current recession took its toll, the industrial face of Dayton has been changing.

An example of this changing face is Dayton Tire & Rubber. After operating in Dayton for almost 40 years, the firm ceased manufacturing in 1980. Its factory complex occupied 37 acres in the northwest part of the city, adjacent to a low-moderate income residential neighborhood. In addition to several stacks, towers, tanks, rail siding and outbuildings, its main structure covered over 1.3 million square feet.

When the plant closed, it left a residue of potentially hazardous materials on-site, including asbestos and PCBs in electrical transformers. In its existing condition, it represented the largest, and worst, public nuisance structure ever confronted by the city of Dayton, and one of the largest in the country.

In 1981, the plant and its remaining contents were sold by the Firestone Company to tire equipment brokers. This group purchased the real estate to house the equipment until it could be sold off. However, the tire equipment brokers were unable to maintain their mortgage and, in 1986, the site was abandoned. No maintenance was performed on the facility during this period. As there was no security on-site, vandals soon took over. Fires were started by copper scavengers. Others, interested in scrap metal, hauled truck loads out without being stopped. As the structure’s deterioration continued, neighborhood complaints to police increased rapidly.

In April of 1987, a city of Dayton employee reported an oil spill on Wolf Creek, a stream running parallel to the site and emptying into the Greater Miami River. The same day, the U.S. EPA seized control of the site.

Subsequent investigations resulted in the discovery of 14,000 gallons of PCB contaminated oil in the abandoned transformers. Piles of friable asbestos material littered the site from when vandals scavenged pipes from the plant’s mechanical systems.

The federal EPA spent the next two years and $5.4 million to remove the PCBs and friable asbestos from the site, and to encapsulate in place some of the remaining damaged asbestos-containing pipe wrap.

It wasn’t long afterward that the vandalism and looting started up again. The remaining encapsulated asbestos was being ripped open by the scavengers. Large holes in the structure’s roof accelerated the asbestos deterioration. Soon children were seen playing inside the complex, having gained access through the numerous holes in the perimeter fence.

The city of Dayton appealed vigorously to the EPA for additional assistance. Municipal officials made numerous trips to EPA Region V in Chicago and to headquarters in Washington to plead for federal aid.

Finally, Dayton’s city manager convened a landmark town meeting with representatives from the business community, lenders, educational, religious and neighborhood leaders to solicit ideas on what to do about this growing neighborhood nightmare.

A series of options were discussed at this meeting, which included cleanup and industrial reuse of the site, or site clearance and reuse as an industrial park, residential use, commercial reuse or open space. The consensus at the meeting was that the city, alone, would have to shoulder the burden of abating this public nuisance, first by removing all the asbestos, then demolishing the structure. A decision was made to clear the site and allow for a “healing process” to take place.

Early cost estimates of $4 to $5 million staggered the city. As with most municipalities, Dayton has been struggling during the current economic downturn. However, a courageous decision was made to reorder some budgetary priorities and dig deep down into their municipal coffers to deal with this problem.

In October of 1991, the city awarded contracts for $921,500 to remove the asbestos.

In late January of 1992, NDA charter member S.G. Loewendick & Sons Inc. of Columbus, Ohio, was awarded a contract to demolish the site. The project’s start date became “D” Day in Dayton, Ohio. On Feb. 11, 1992, dignitaries, including the mayor and city council of Dayton, held a ceremony on-site and cut a ceremonial ribbon with one of Loewendick’s bulldozers to kick off the project. Dayton Mayor Richard Clay Dixon declared “We’re pleased to finally see this day come. But, at the same time, it is disheartening to know that there are similar sites throughout our community. Local governments can not continue to bear the cost of these projects alone. I am pleased that the city of Dayton was able to step forward and take action. This will make a positive difference for the neighborhood. I hope we do not face these same nightmares in the future.”

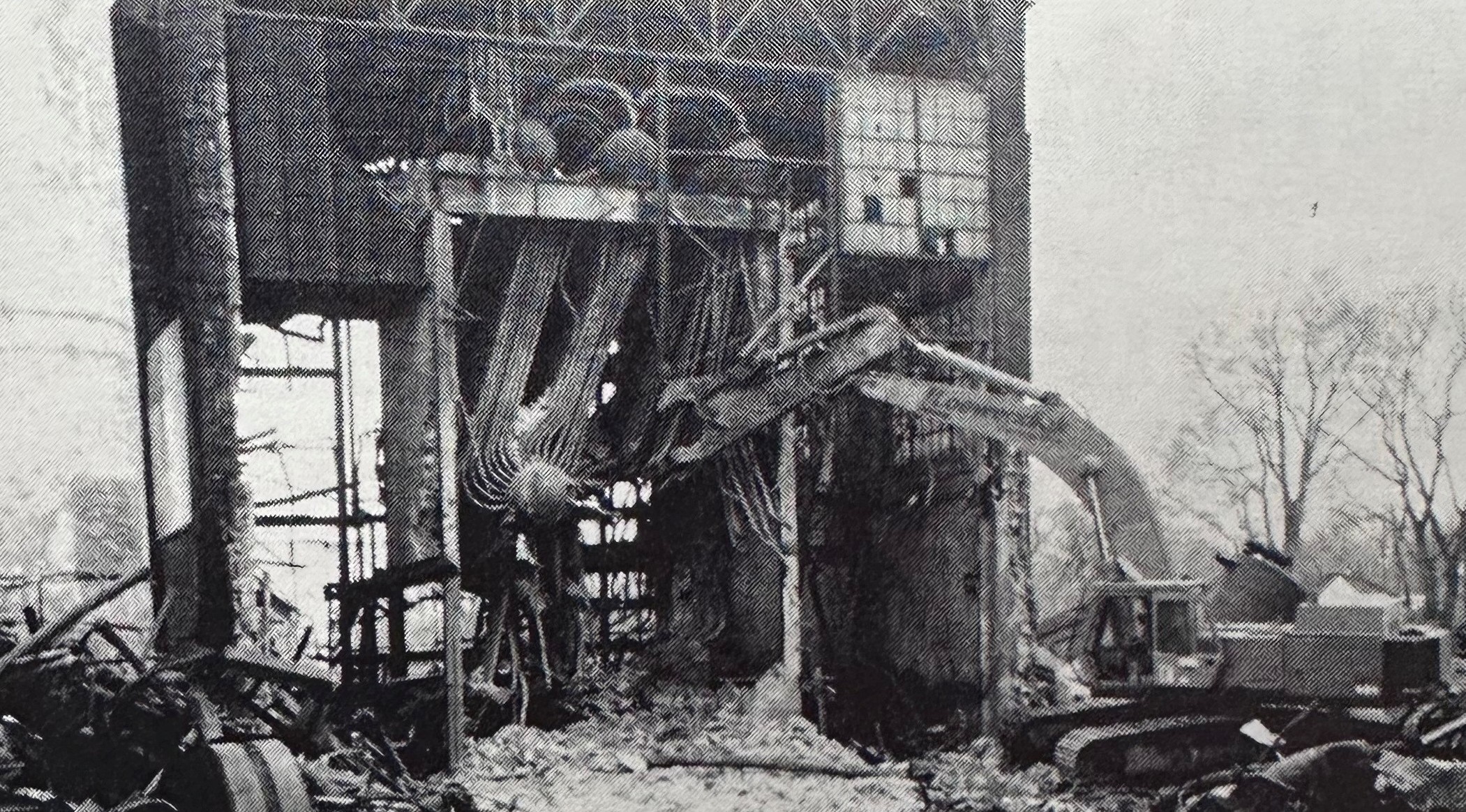

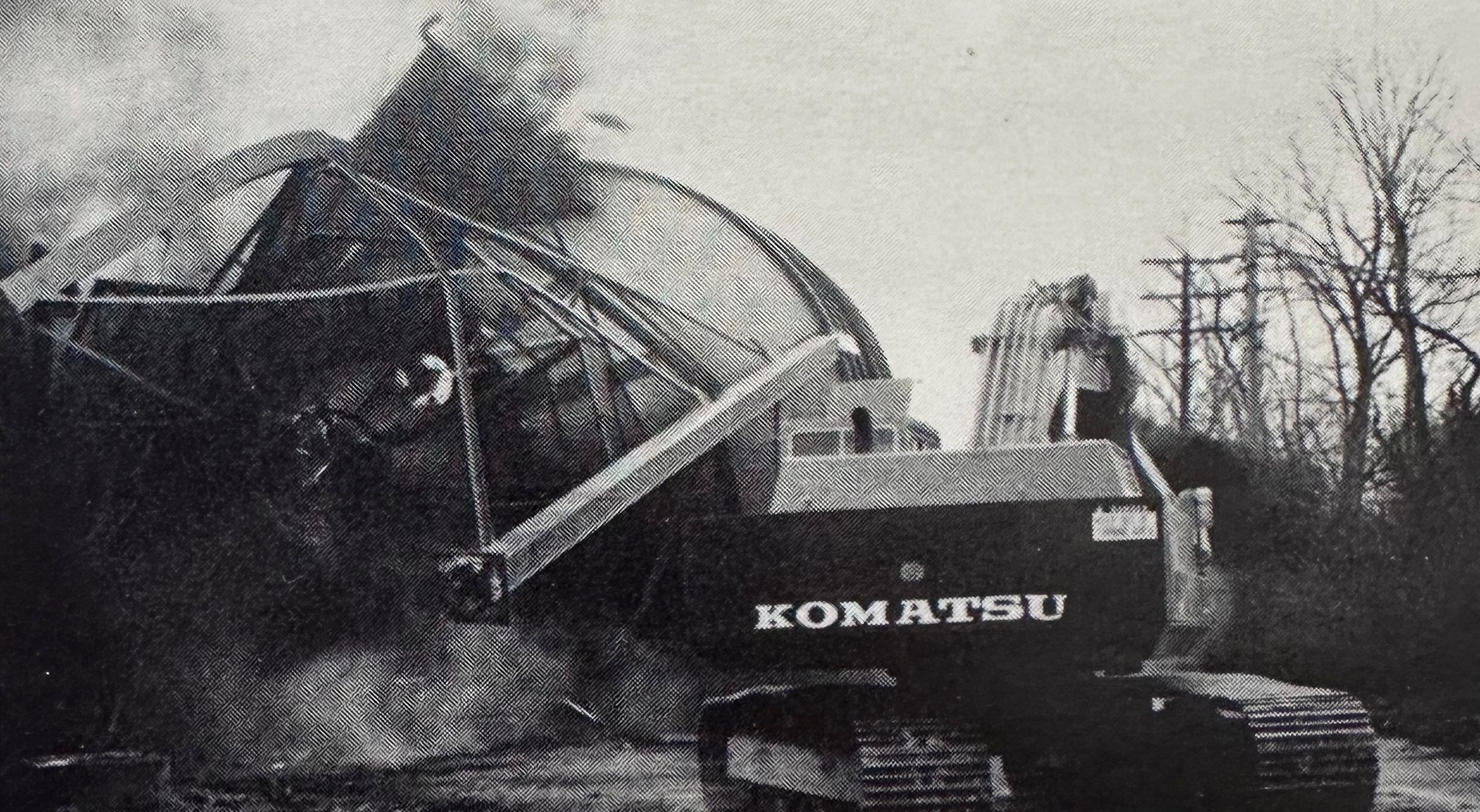

The demolition has gone well from the start. Beginning with eight pieces of heavy equipment, eight semi-size hauling trucks and 21 people, Loewendick put the project well ahead of schedule early. Using LaBounty grapples and shears on Komatsu hoes, Loewendick superintendent Harry Keith picked and snipped his way through the outbuildings and main plant, separating and stacking more than 6,000 tons of twisted steel, concrete, brick and other materials. The vast majority of the debris is being recycled, salvaged or scapped. Loewendick has removed the plant’s boiler house, a large carbon black tank, a 135-foot water tower and the facility’s 150-foot smoke stack. Loewendick will be lowering the site to grade, filling many of its larger holes with backfill imported from offsite. It will be top soiled and seeded for use as open space by the neighborhood.

While the firm has until December 1992 to complete the work, Vice President R. David Loewendick of S.G. Loewendick & Sons reports that they are well ahead of their schedule and expect to complete the project before the fall, under budget.

The challenge for the demolition industry and the nation is that the tale of Dayton Tire & Rubber is all too typical. As the industrial face of America changes, the problems of abandoned plants will grow. The environmental and economic challenges they present will have to be handled in a comprehensive and professional manner. Dayton Tire & Rubber is a success story because of the efforts of enlightened civic leaders, municipal officials, neighborhood representatives and a knowledgeable, resourceful demolition contractor. The success of similar projects will depend on assembling the same type of team with the will, determination and talent to turn a public nuisance into a public improvement.