Restoring the Gettysburg Battlefield

June 25, 2024

This article originally appeared in the September/October 2000 issue of DEMOLITION magazine.

To realize the real horror wrought in the farm fields of central Pennsylvania during the first three days of July 1863, imagine the dead and wounded men, including those listed as missing, evenly distributed over 15 square miles of the entire battle area. The result would be more than 1,600 men to every square mile. Grimmer still: Imagine that of the 160,000 who faced each other across those terrible open fields, more than one in four lay dead or horribly wounded at the end of the three days of carnage.

The battle was the largest engagement ever fought on the North American continent. It crippled both armies. Never again would Lee mount a major offensive, leaving too many of his finest men in the shallow trench graves etched in the rocky soil of Gettysburg.

The unwilling draftees and unreliable bounty men who filled the ranks of the depleted Union army were hardly equivalent replacements for the men who died on McPherson’s farm and the shallow slopes of the hills surrounding this tiny college town. It was the last great battle of volunteers fought in the East.

Lincoln’s famous address to the nation at the dedication of the cemetery at the battlefield remains one of the great American speeches.

As the site played such a pivotal part in the nation’s history, preservation of the battlefield in its original state has always been an important issue. Preservationists and the federal government have decided that visitors can better appreciate the enormity of the 1863 events if the site is restored to what it looked like back then.

For years, preservation groups have been collecting funds to rid the battlefield of telephone lines, modern structures and new roadways. Plans have been recently approved to consolidate many of the existing displays and artifacts in a new visitors center to be built near the site where Lincoln delivered his famous address.

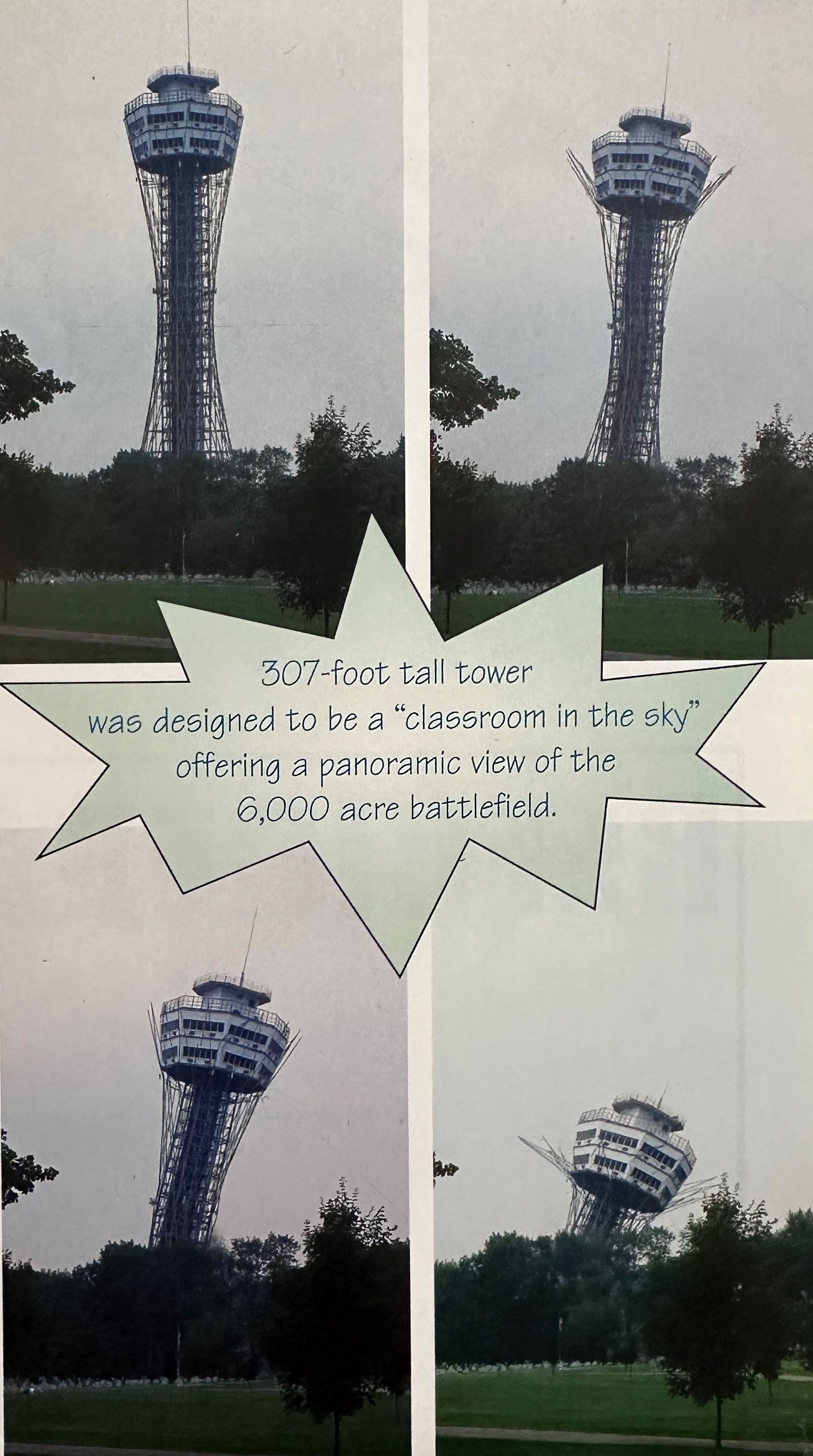

One of the most controversial structures on the site has been the so-called Gettysburg National Tower, which overlooked the battlefield near the famous Culp’s Hill. Opened in 1974, the 307-foot-tall tower was designed to be a “classroom in the sky” offering a panoramic view of the 6,000-acre battlefield.

Controversial from its very inception, the tower became a lightning rod for preservationists who wanted the hallowed fields of Gettysburg to look as they did some 137 years ago. The Department of the Interior has vowed to remove the structure as part of its overall master plan for the preservation of the Gettysburg National Park.

The battleship gray tower was imposing. It contained over 5 miles of steel latticework held together by over 14,000 bolts and anchored in a granite base by 15,000 tons of concrete. Its unusual shape, a narrowing waist in the middle, had been compared to the Space Needle in Seattle. The whole structure weighed over 2 million pounds and was topped with a quartet of viewing decks that could accommodate up to 750 people.

The battleship gray tower was imposing. It contained over 5 miles of steel latticework held together by over 14,000 bolts and anchored in a granite base by 15,000 tons of concrete. Its unusual shape, a narrowing waist in the middle, had been compared to the Space Needle in Seattle. The whole structure weighed over 2 million pounds and was topped with a quartet of viewing decks that could accommodate up to 750 people.

Following decision by the National Park Service that they would take over the tower, NDA member Controlled Demolition Inc. (CDI) and the Loizeaux family of Baltimore, Maryland, offered to perform the demolition of the structure on a no-fee basis with the net scrap value of around $28,000 going to CDI to help offset its costs.

CDI took the job on a pro-bono basis as it had enjoyed tremendous international success in the explosives demolition of structures over the last half century, and many of those projects have been through U.S. government agencies for the benefit of the taxpayer. Their assistance in the removal of the National Tower was their way of giving something back through the National Park Service, a federal agency that is solely devoted to furthering the American people’s appreciation of our natural resources and cultural heritage.

The National Park Service’s original budget for the dismantling of the tower in its small 125- to 150-foot print was around $1 million. That alternative figure would make CDI’s pro-bono services the single largest corporate contribution toward preservation at Gettysburg National Military Park in the park’s 105-year history. CDI’s donation, made through the nonprofit preservation and advocacy group The Friends of the National Parks at Gettysburg, was actually far less from an explosives demolition standpoint. The estimated value for CDI and those others who volunteered their time for adjacent property surveys, seismic monitoring, and security and traffic control was something in the range of $200,000.

CDI made a structural survey of the tower in June and found the tower to be 3 feet out of plumb and twisted 7 degrees at the top. Those structural deficiencies created problems for CDI, requiring the tower be telescoped more vertically than originally planned.

CDI used less than 15 pounds of explosives to start the initial rotation of the hyperbolic structure before starting its vertical collapse. They used RDX linear-shaped charges placed at 17 locations around the tower’s lower 35 feet. The tilt and twist of the tower’s observation platform created shear loads, which the existing structure could not tolerate if left to fall its full height, like a tree, through a 120-foot-wide neck of land that the National Park Service controlled between the base of the tower and the adjacent parking lot.

The telescopic shot plan allowed the tower to fall vertically, landing just short of adjacent wooded property that was privately owned. That property owner was prepared to permit the tower to fall on their land, as site cleanup and replanting was promised by the National Park Service. CDI’s handling of the structural anomalies proved adequate to eliminate any replanting requirements.

Seconds before the implosion, Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt gave orders to men dressed in Confederate gray and Union blue uniforms – Civil War reenactors at Gettysburg for the battle’s anniversary – to fire point blank cannon rounds toward the tower. Babbitt said: “This is sacred ground. Americans come here to learn of their past … their heritage. It is our obligation to honor this sacred land by preserving it.”

Salvage of the 1,000 tons of galvanized steel was subcontracted to fellow NDA member Mayer Pollock Steel Corporation of Pottstown, Pennsylvania. Mayer Pollock’s Mickey Pollock and Steve Abrams felt that the cleanup, shearing, stockpiling and ultimate sale of the scrap would take less than 90 days.