Geppert Bros. Brings Down Philadelphia’s Naval Hospital

July 30, 2024

This article originally appeared in the July/August 2001 issue of DEMOLITION magazine.

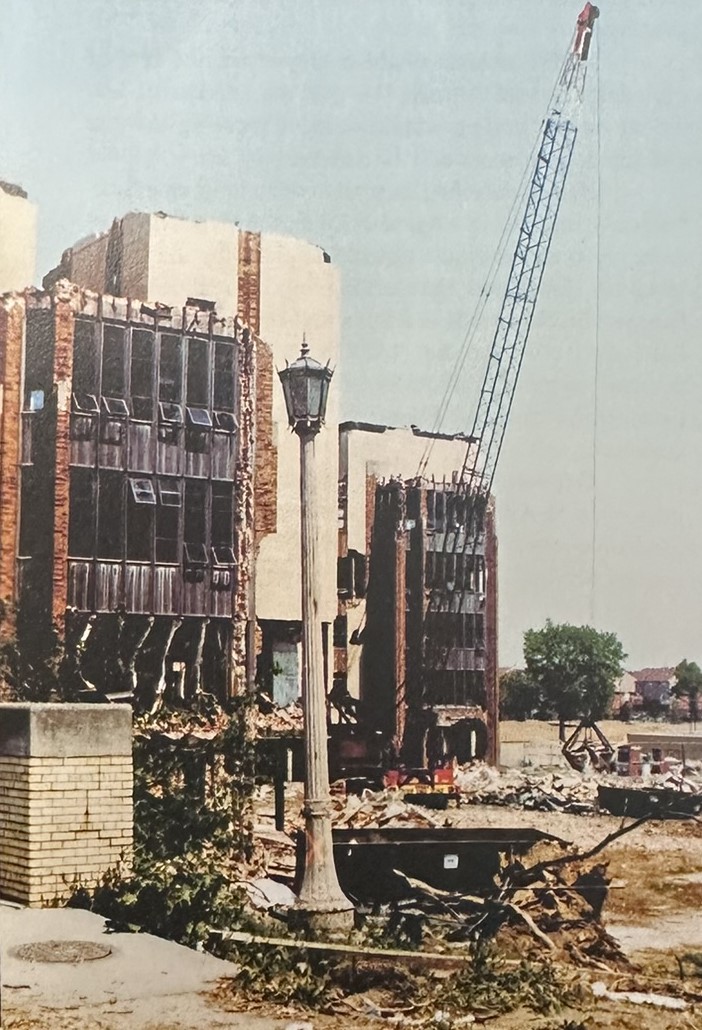

For 66 years, the U.S. Naval Hospital in Philadelphia stood close to the oldest shipyard in the country and ministered to the needs of sailors of their country. Built in 1935, the art deco building had 12 floors and a total height of 15 stories. Capped by two battlement-like towers where the U.S. and Navy flags constantly flew, the hospital was massive, containing over 650 beds.

Often thought too large, the facility proved vital during the nation’s greatest challenge, as it was the main hospital on the East Coast for naval and marine personnel during World War II. At times during the war, over 3,000 patients were housed in the facility, severely taxing its resources and staff.

The Naval Hospital became famous as one of the leading centers for dealing with traumatic wounds and the development of prosthetic devices. It also changed the way injured military personnel were treated, moving them into large wards where they would enjoy the company of other wounded comrades rather than the practice of the day of isolating each Marine or sailor in an individual room. This innovative treatment proved extremely successful in dealing with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) so common among wounded military personnel.

By the time of the Vietnam War, the hospital had grown to 1,100 beds and remained one of the country’s leading facilities dealing with prosthetic devices and the treatment of PTSD. Former U.S. Senator Bob Kerry, who spent nine months recovering at the hospital after losing part of his right leg to a grenade, called his time there “a remarkably positive experience for me, all in all.”

“It became a very special community. There was a lot of pain and a lot of adjustment and a lot of tears, but it felt like a family there,” said Kerry, who remembers the fishing trips organized by volunteers and invitations to their homes.

James J. Kirschke, now an associate professor of English at Villanova University, lost both his legs in Vietnam and has written a book titled “Not Going Home Alone: A Marine’s Story.” Kirschke spent more than a year at the Naval Hospital, and his book includes memoirs of his time recuperating at the facility.

Pennsylvania State Supreme Court Justice Ronald P. Castille, who served as District Attorney of Philadelphia, spent over a year at the Naval Hospital mending from the loss of his right leg in a Vietnam firefight.

In the late 1980s, the Navy realized that the facility was just too large for its needs and began to evaluate alternative uses. Attempts were made to attract developers who might consider turning the hospital into apartment units or luxury condominiums.

Considered one of the premier examples of art deco architecture in the city, the Naval Hospital suffered most from its somewhat isolated location. Although it was across the street from Philadelphia’s Franklin Delano Roosevelt Park, it was far from the beautiful paths of the park itself. Located in South Philadelphia, just north of the Naval Shipyard, it missed the bustle of center city Philadelphia. With the birthplace of the American Navy located in the Independence National Historic Park and a statue of John Barry, the founder of the U.S. Navy, located just south of Independence Hall, the hospital was part of the strong Navy tradition of Philadelphia yet strangely removed from it. When the annual Army-Navy football games were held at nearby JFK Stadium where the First Union Center, home of the Flyers and 76s, now stands, patients at the hospital would be brought over to attend the game.

While the tight-knit South Philadelphia neighborhood surrounding the hospital hoped for a new use for the facility, they realized that its sheer size made marketing its reuse difficult for the city. The Navy divested itself of the hospital and its 48-acre site in 1993, and the facility has been dormant for eight years.

Finally with the redevelopment of the nearby Sports Complex district, which includes new stadia for both the Philadelphia Eagles and Phillies, the city made the decision to demolish the structure for use as a temporary parking facility for the 1,500 construction workers it expects to build the new playing fields for the two pro teams.

NDA charter member Geppert Bros. Inc. of Philadelphia and Colmar, Pennsylvania, was the successful low bidder on the project, which included clearing the site and the development of a 10-acre parking lot.

Because the Eagles plan to open the new football stadium in August 2003, the Geppert Bros. were given an extremely tight schedule to get the Naval Hospital down and the parking lot up and running. Geppert brothers, Bill and Dick, and Dick’s wife, Mary Pat, who serves on the NDA Board of Directors, decided to retain fellow NDA member Controlled Demolition Inc. (CDI) of Phoenix, Maryland, to implode the structure.

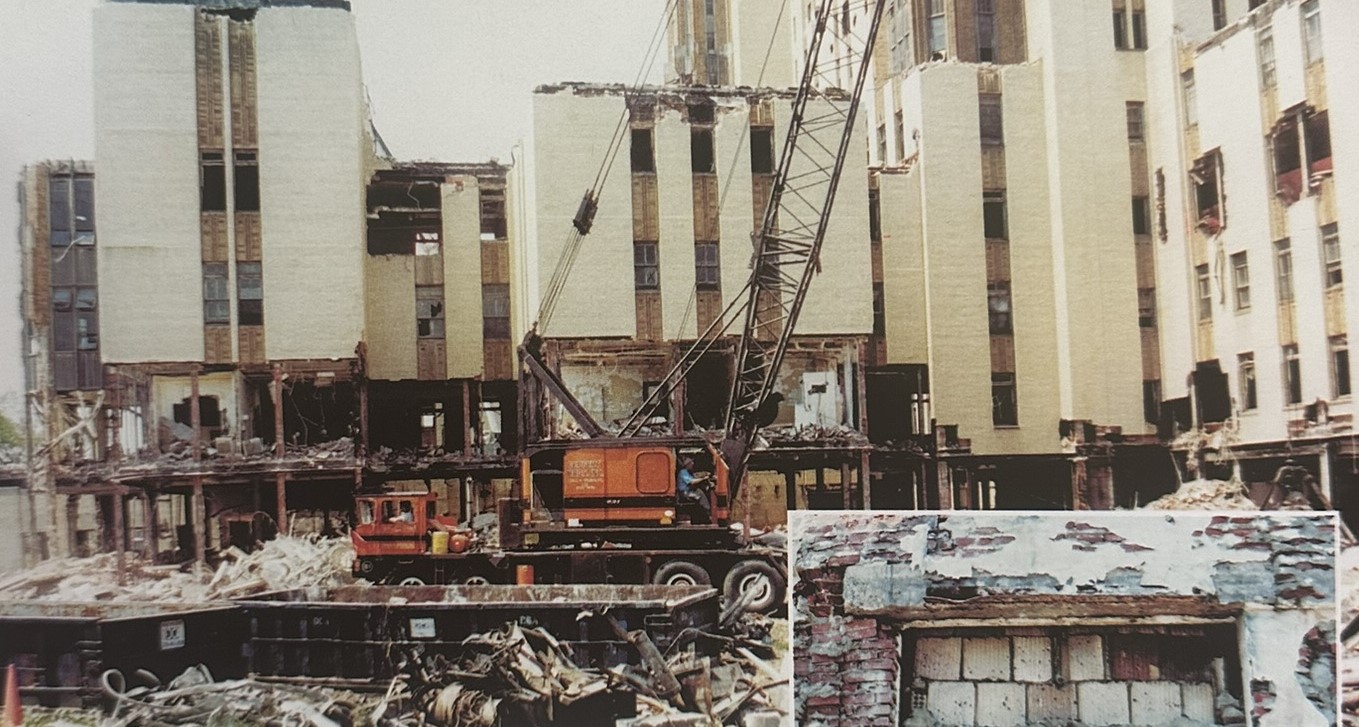

Geppert Bros. began to prepare the structure for implosion in April. A considerable amount of the pre-implosion work involved dealing with the asbestos that proved pervasive throughout the facility. Geppert Bros.’ asbestos abatement subcontractor removed the insulation material from all the mechanical systems, boiler rooms and roof areas. The implosion had to be delayed for an additional two weeks to deal with additional asbestos-containing material found during the demolition.

Bill Geppert remembered that during the early 1930s, his father had demolished the previous Naval Hospital, which had been in a series of small wooden structures located inside the U.S. Naval Shipyard. All this work was done by hand, and the young Bill Geppert, all of 10 years old at the time, was assigned the task of signing in and out the tools required by each worker to complete the demolition. Bill remembers that much of the salvageable material that came out of the original Naval Hospital project was bought by Amish buyers who would journey to Philadelphia from Lancaster County and purchase building materials they thought they could use. Geppert Bros. would deliver the salvaged materials to them.

Another interesting element of this project was that a film crew from the Arts & Entertainment Network, A&E, was in Philadelphia to film the project as part of a two-hour documentary on demolition, tentatively to be called “The Wrecking Ball” and scheduled to run in the fall. The Loizeaux family has been working with A&E’s producers, and the show may focus on three of their projects, including the Market Square Arena in Indianapolis, the Keyspan Gas Holders in Maspeth, New York, and a third project yet to be selected.

On Tuesday, June 5, 2001, CDI conducted a test blast to determine the structural nature of the facility and to acquaint the surrounding neighbors with what they could expect on June 9.

As Geppert Bros. rushed to complete the pre-implosion preparations of the facility, CDI prepared the Naval Hospital with some 250 pounds of explosive material.

At exactly 7 a.m. on a beautiful Saturday morning, June 9, 2001, Doug Loizeaux and Thom Doud of CDI ordered the implosion sequence and Richard Geppert forever changed the skyline of Philadelphia. Scores of retired veterans and former civilian employees of the facility watched, some sadly, as their old home disappeared into history.

The Geppert family and Doug Loizeaux were all extremely pleased with the success of the implosion. As the dust cleared, the Naval Hospital stood in a neat pile ready for processing and recycling. Most of the concrete from the facility will be used as fill material and sub-base for the temporary parking lot and the metal portion will be sent to a nearby scrapyard for reuse. Geppert Bros. purchased a brand-new 1000 15 CV Stealth unit from NDA member Eagle Crusher Co. Inc. of Galion, Ohio, to process the mixed loads on-site.

Once the two new stadia are completed in April 2004, the city of Philadelphia will consider new uses for the site, which may include the development of residential housing or new parkland.